Some "Cures" for High PitchThe period just after the release of Boehm's cylinder flute brought a flood of interesting new flutes. Some of these employed Boehm's new bore, but the old 8-key format. Others were based on Siccama's 10-key arrangement; others were fully keyed but still operated as 8-keys, and still others featured tricks to improve venting and facilitate fingerings. All fascinating stuff. Unfortunately, many of them are of little practical use today - they are stuck at Old British High Pitch! Who wants to play with you when you are just over half a semitone sharp? What was High Pitch?High Pitch was a fiendish folly perpetrated by the Philharmonic movement in Britain. Higher pitches made for more vibrant sounding orchestral performances, even if at great personal risk to singers, fiddles and pianos. There seems some evidence to suggest that the woodwinds were to blame. Shame! The actual pitch varied with time in the region A= 447 to A = 455Hz, over the period 1850 to about 1880. It was then killed off in the Philharmonic arena in the 1890s, but continued well into the 20th century as Band Pitch. You can see more in The Rise and Fall of English Pitch. And the problem?The problem for a lot of these post-Boehm flutes is that, unlike 8-key flutes, they employ extremely short tuning slides, integral with the top tenon. When we try to pull the head out far enough to get down to modern pitch (A = 440Hz), the head falls off somewhere around the 445 region. Clearly the makers were confident in the longevity of High Pitch! Strangely, 8-key flutes made at the same time and even much later continued to be made with a very long tuning slide, permitting about 30 Hz variation. Both flutes could get up to around A = 461, but only the 8-keys could get down to modern pitch. A Lost Cause?Well, it's just tough luck isn't it? Surely there are two fairly insurmountable problems:

The tuning issueIn theory, extending the head far enough to get A down to 440 Hz should really screw up the tuning of the flute. Lower notes would go painfully sharp, higher notes flat. But, surprise, surprise, this never seems to be the case. Indeed, testing a number of these style of flutes at High Pitch, we find the low notes flat and the high notes sharp. When we can conspire to give them a decent length of head, the intonation is usually considerably better, often stunningly good. To illustrate, look at this chart from a Ball, Beavon & Co flute:

The dark blue trace is with the head right in. The Red trace is at 8mm extension - about as far as you could extend it without the head falling off. The Yellow trace is with a longer head from another flute. Clearly, the flute worked better at the lower pitch. Why, is hard to fathom. It's tempting to believe that the makers simply shortened the heads of existing designs to achieve High Pitch, rather than rescaling them fully. But we haven't found any low pitch versions of these flutes to consolidate that view. Anyway, don't complain - it works to our advantage. The tuning slide issueSo finding a way to extend the tuning slide becomes the big issue. If we can find a way to extend the head, we can rehabilitate flutes that have lied unwanted and unloved since the mid-to-late 19th century. Let's take a look inside one of these slides. A typical slide/tenon combination: |

||||||||||||||||||||||

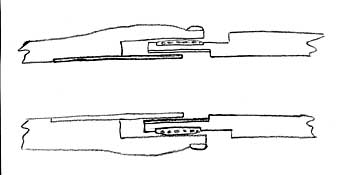

| At the left, you see the lower end of the head, with the

short male slide captive in the wood and protruding into the

socket. On the right is the body tenon, with the short female part

of the slide tucked away inside.

Discreet. Very Victorian! |

|

|||||||||||||||||||||

And, as you can see, there's not much scope

for extending that slide without making the whole thing look

ridiculous. And we're not just talking a few mm here, another 20mm

(3/4") or so would be handy!

Do we give up hope?Good grief, no! These instruments are special, and deserve to live on! I have at least two approaches that can bring about a solution, and perhaps there are more yet to be found. Solution No 1 - the New HeadThis is, I suppose, the obvious solution. It's no big deal to make a new head for one of these instruments. Indeed, there are other attractions of this approach. The English makers were, for reasons best known to themselves, reluctant to take on the improvements to the embouchure and head design that Boehm was making overseas. They stuck to the tried and true "hole in the broomstick" style, which must have suited the Victorian British Stiff Upper Lip. Fit one of these old flutes with a new head with a modern embouchure and you'll need to tighten the buckles on your motorcycle helmet. There's another benefit. The old heads tended to split at the point where the outer metal slide was encased in the wood. The usual problem where the wood shrinks but the metal doesn't. A new head allows the opportunity to employ my New Improved Tuning Slide Mk III technique to prevent that happening in future. Where the slide meets the wood, a layer of tenon cork is interposed. Movement in the wood is taken up by compression of the cork. The other benefit is that the original head remains intact. That might be important if it's a rare instrument, or if you might also want to play at High Pitch for Historically Informed Performance reasons. This way, you can have your cake and eat it too. The image below shows the old and new heads for a Ball, Beavon & Co flute. Comparing the features:

Both heads incorporate a tuning slide concealed inside the socket. Both also have a screw stopper. For information on my new heads for old flutes ... Solution No 2 - a new SlideBut supposing you are perfectly happy with the existing head and embouchure, but just want it to get down to modern pitch? Is there no solution? Indeed there is. Cut the head, just below the head taper, to form a separate head and barrel. Fit the head with a Mk I style male tuning slide, and the barrel with a Mk II female style. If necessary, add some extra length in the form of wood, hidden beneath the wide bands of the Mk I slide. Now obviously this involves taking some liberties with historical fact. If that's a problem, we go back to Solution # 1. But indeed, are the liberties that extreme? We haven't actually tampered with the bore or other fundamental aspects of the instrument, just enabled the head to extend a bit further. Now why, you might ask, use a Mk I slide on the head end? Because, the bore of these heads is tapered, and nobody has been able to make a tapered tuning slide! The MK I slide is fitted externally, where it doesn't endanger the all-important head taper. If you go that path, what happens to the original tuning slide, tucked away inside the socket? If it's all intact, it can probably stay there. If however, as often is the case, splits have occurred where the slide is encased in the head, it might be better to pull it out, glue the cracks closed and replace the slide (in the area that was encased in the head) with a tube of wood of similar dimensions. As the wood will move with the weather, no further problems should be noted. Indeed, the whole new wood will reinforce the old split wood, greatly enhancing its strength. That leaves the top of the body with the empty socket - not a good thing for intonation. An off-cut of the old slide can be used to fill the vacancy. If however, splitting has also occurred on this side of the divide, the same strategy can be used - pull out the slide entirely and fill the gap with a wooden tube. The socket and tenon joint will now be just that, with no integral slide to cause further problems. I don't have a picture at the moment of how Solution No 2 turns out - I'll bring you one next time I do such a job. ConclusionsIt is possible to breathe new life into the magical old flutes of the immediate post-Boehm period. Deciding how best to do that will require weighing up the issues in each case. |

||||||||||||||||||||||