Siccama's 1-key Flute

|

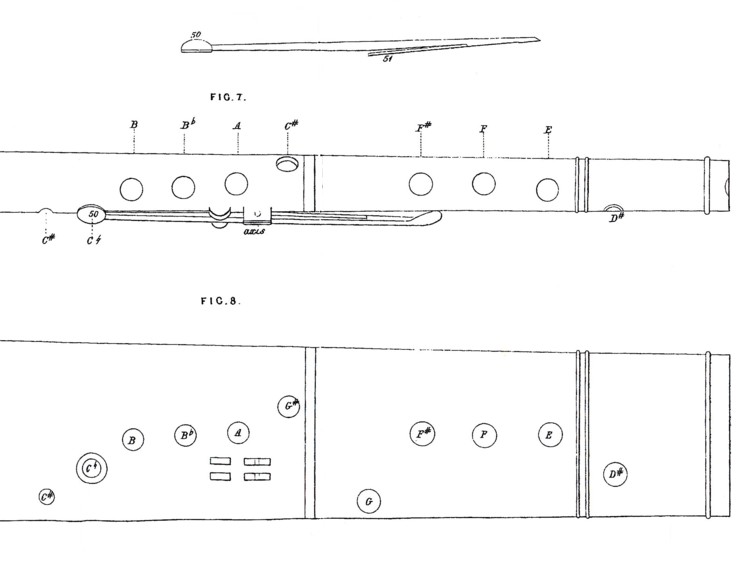

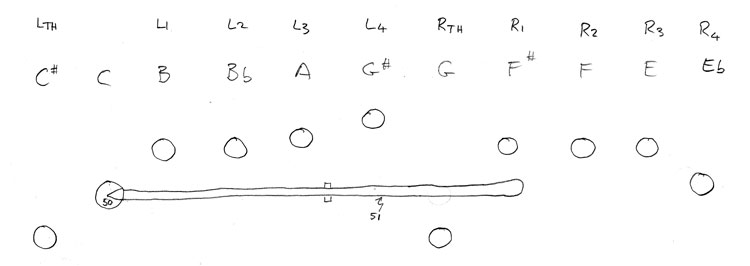

| Note | Lth | C-key | L1 | L2 | L3 | L4 | Rth | R1 | R2 | R3 | R4 |

| D | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X |

| Eb | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | |

| E | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||

| F | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | |||

| F# | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||||

| G | X | X | X | X | X | X | |||||

| G# | X | X | X | X | X | ||||||

| A | X | X | X | X | |||||||

| Bb | X | X | X | ||||||||

| B | X | X | |||||||||

| C | X | O | |||||||||

| C# | O |

with the second octave essentially the same as the first, with maybe the addition of a few extra vents, eg the 2nd octave D becomes:

| D' | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X |

But supposing it proves impossible to hold the flute reliably on a fingering such as:

| C# | O |

Arghhh! Every finger and thumb off and the only key pressed open! What holds the flute up?

I'm expecting that, as we come to grips with this flute (so to speak), we may need to modify the fingering from the theoretical to the practical. Perhaps that can be accomplished without materially affecting the venting (eg by leaving two holes in a row open, then closing one after that to support the flute), but it might be that it can't. If not, we can expect to need to adjust hole sizes to compensate. But that's OK, we have plenty of room to move.

The Real Thing

So, here's the real thing. Perhaps the first Siccama 1-key Chromatic Flute since the late 1840's. Or indeed, perhaps the only Siccama 1-key Chromatic Flute ever made! Do I hear Rockstro chuckling from the Beyond? What's that sulphurous smell?

How does it feel?

Well, I'll admit to a person who has played Irish style flute for 35 years, decidedly odd. But not impossible to hold, so hope remains.

Indeed, the stretches are negligible, unlike the baroque 1-key or the romantic 4 to 8-key flutes. So stretch is not the issue. I suspect the issue will arise when not covering holes, rather than when covering them.

And how was the tuning?

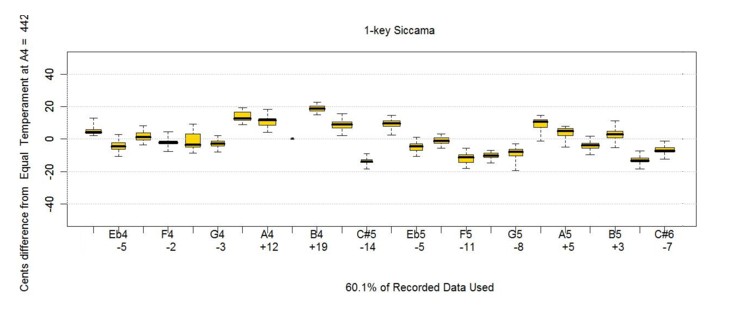

Not bad at all, especially for a first prototype based on an unscaled drawing from a 164 year old patent application! The chart below was prepared by Real Time Tuning Analysis with me blowing the "fully vented" fingering pattern (as shown in the chart above).

I've just looked at the first two octaves for now - the third octave will take more investigation. But given the availability of fingerholes at every semitone, I'd expect we'll have little difficulty in finding satisfactory fingerings up there.

We shouldn't see the chart above as an indicator of how good was the tuning of the original flute (if it was ever made!). I'm confident we could get that tuning much better - perhaps almost perfect - by modifying the bore (remember we just used Siccama's Diatonic Flute bore as our jumping off point). After all, just like Boehm's conical flute, we have a hole for every semitone and the holes are spread at acoustically appropriate distances.

How does it compare?

It's very interesting to contrast the performance of Siccama's 1-key with the Baroque 1-key flute (which is perhaps the fairest comparison). Nowhere on Siccama's flute do we see the challenging tuning problems that bedevil the baroque flute - eg the F# that is 40 cents flat and the F natural that is 40 cents sharp. And all the notes are clear and full, unlike say the dismally weak Bb and G# on the baroque instrument.

(Baroque 1-key players and makers are probably bristling a bit at this point! The baroque 1-key is certainly capable of being played most deliciously, but such success is a tribute more to the player, rather than the design. In Siccama's period, flute players were looking for volume and intonation that the baroque flute could not deliver. 1-key flutes continued to be made, but not for serious music makers.)

Even the English romantic period 8-key, the forerunner to the modern Irish Flute, has notes that are hard to get as accurate as our first attempt at Siccama's 1-key has achieved. F# and C# are often -30, while our prototype has contained everything within 20 cents. With the promise of better to come if we wanted to proceed with it.

What happens next?

But before we go fiddling further, we need now to answer the BIG QUESTIONS:

-

could a player learn to play and enjoy a flute with this layout?

-

would any minor changes to hole positions substantially improve the ergonomics?

-

could the player employ the theoretically desirable "fully vented" fingering pattern, or would practical issues (like being able to hold the flute securely) require adopting a compromise fingering pattern?

-

would the compromise fingering pattern substantially alter the tuning?

-

are there any cross-fingerings that would be of particular value in say fast passages that almost work but deserve mining for?

-

are there any insurmountable problems finding third octave fingerings that work?

These are questions for players rather than makers to tease out, so it's time now for our reconstructed flute to leave the nest and nervously take its place among the flutes of the world. If the system seems viable but changes need to be made to make it easier or better, there is nothing I can see that would prevent that happening. That's in contrast with say the baroque 1-key or the Romantic 4 to 8-key flute where there are statutory limitations that cannot be easily overcome.

Other attempts at keyless and nearly keyless flutes.

If, about now, you are thinking this whole thing has surely been a fool's errand, it's time to remember that many have sought the elusive goal of a totally keyless (or even mostly keyless) fully chromatic flute. In chronological order, we can point to at least:

-

the baroque 1-key, reigning unchallenged through the 17th and 18th centuries. It approximated a chromatic scale, demanding much from the player to lip notes up or down as needed.

-

Tromlitz, around 1800, talks about designing a better 1-key flute with only a Eb key, but concludes that, while it is possible, the fingering becomes very difficult.

-

Pottgiesser, in 1803, published a suggested plan for a single keyed flute in which the right thumb operated the Eb key, all other notes being controlled by the remaining thumb and fingers.

-

Dr Burghley, a gentleman flute maker of Camden Town in London, circa 1845, produced a range of flutes with no or few keys. Examples can be found in the on-line catalogue of the Dayton C Miller Collection.

-

Signor Carlo T. Giorgi patented a vertical flute made in ebonite by Wallis in London and Maino & Orsi in Milan. This could be keyless or have several keys. Every available digit and even the side of the hand was pressed into service in Giorgi's keyless version.

-

Modern maker Skip Healy produces a 10 hole keyless chromatic flute, essentially a keyless Irish flute with the missing chromatic notes assigned to the remaining fingers.

-

There may be others I've missed - be sure to let me know!

So it wasn't just a Siccama obsession - indeed, it's the Philosopher's Stone of flutemaking. Every open-hole flute player knows that keys seem clumsy compared to the elegance of the simple hole. But coming up with a viable system has proved a difficult challenge. Time permitting, we'll look at some of these other approaches and compare them with the Siccama.

So what will players think?

I've made reaction to Siccama's 1-key

the subject of a separate chapter...

Acknowledgements

To my research colleague Adrian Duncan, for commissioning the project. And to the Library of Congress, British Library, Glasgow University Library and the UK Patents Office for keeping and providing copies of Siccama's treatises.